It’s crisp, crunchy, and salty — and you’ll never find it in a bag in the grocery store. Dipped in seal oil or eulachon oil (hooligan), it is a traditional Southeast Alaskan delicacy that signals spring as surely as a warm, sunny day. But, gathering herring eggs-on-hemlock branches is about a lot more than food.

ANB Harbor. Stall 10. Small boat on the left. That’s Chuck Miller’s response to anyone looking for herring eggs. Miller has the means to harvest this traditional food in the traditional way. So, sharing the resource is a no brainer. “Food tastes better when you share with people and that’s the way our Native people are,” says Miller.

Like many subsistence fisherman, Miller practices the roe-on-hemlock harvesting method. He invited me to join him and his son, Jay, on a recent harvesting trip.

Miller: We are ready to get some fuel.

EF: With the fuel and everything how much does a trip like this cost you?

Miller: Over 200 dollars easy but it’s worth it.

That includes engine repairs and two trips out to Middle Island. Miller says it’s worth it because he’ll end up feeding at least a dozen people. But within minutes, I learn that he has deeper reasons for the practice. Jay explains.

Jay: The first time I went out I was 6 years old.

EF: Do you remember what that was like?

Jay: Yeah, I went with my uncle Eli my Dad’s brother.

Miller: The yellow buoy that’s on there is my brother’s buoy and my brother’s been passed away now for ten years. He was 5 years older than me. We used to do this together. This is the last of the gear that he had that he used.

As we pull into a cove on the backside of Middle Island the water abruptly changes from deep blue to a milky aqua. That’s what happens when you add a whole lot of fish sperm — or milt — into the mix.

Miller: So it is still spawning in here.

Plastic bottles and milk jugs speckle the shallow water – all tied to submerged hemlock branches. A handful of those have “Miller” written on them in bold black sharpie ink.

He says people have stolen his sets in the past – which isn’t unusual when branches are left unsupervised overnight to gather eggs. As a result he’s mildly apprehensive around other fisherman.

Miller: He’s probably just staring me down because he doesn’t know who I am. But I’m gonna let him get a good look at me because I lived here my whole life.

Miller has a way of diffusing the tension.

Miller: Hey are you taking my sets? Haha! You guys look like you got a good set in!

Miller: K it’s coming up on your side. Right there, right there, right there!

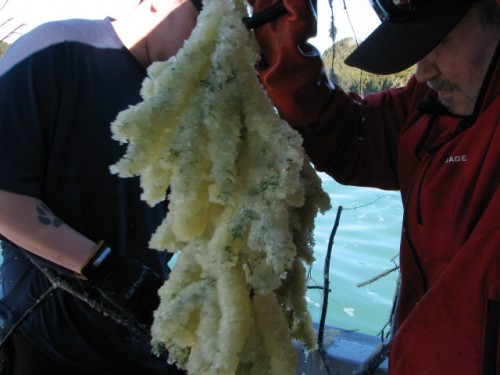

Jay grabs the milk jug attached to his Uncle Eli’s yellow buoy. He clutches the trailing thick rope. Using all of his body weight he wrestles the egg-laden branch to the surface.

Miller: Get it to where you got some leverage. is it moving? It’s probably super heavy?

When its ready to harvest, a branch can weigh well over 400 pounds.

Miller: What we do is clip off pieces of it to get it in the boat. Holy smokes! That’s a good one right there!

Miller hoists the dripping branch into the boat. It’s coated with eggs and looks like it was dipped in a vat of rubber cement.

Miller: See this is the thickness you want, some people get them a little thicker, but not much more than that.

It’s a bountiful harvest, which according to Miller is thanks to his brother’s buoy.

Miller: It’s my good luck buoy and usual that’s the one every year that produces quite a bit it’s like my brother is looking out for us.

He tosses the leftover branch overboard.

Miller:Gunalcheesh! Thank you! We used the tree to help us.

Take away the power boat, and plastic milk jug buoys, and it isn’t difficult to picture this practice taking place long before Western and Native cultures met.

Miller: If i don’t start sharing what I know right away… I might not be here tomorrow.

When we return to ANB harbor, and pull into Stall 10. I realize that gathering herring eggs on hemlock branches is an expression of gratitude. Gratitude for the the teachings of his ancestors, gratitude for food, and the chance to pass on this way of life.