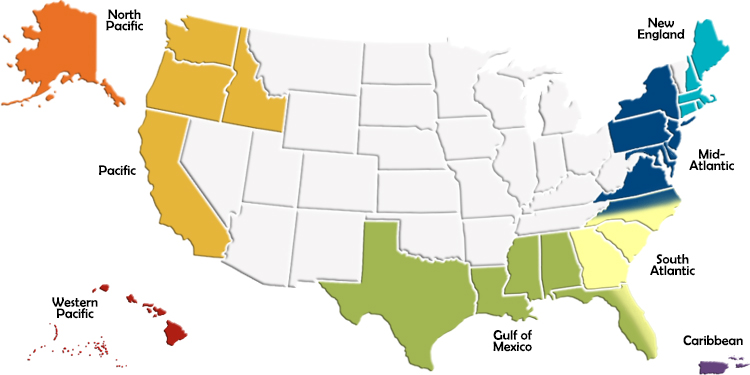

Magnuson-Stevens created 8 separate regional councils to manage fisheries in federal waters. According ALFA’s Linda Behnken, not all regions have placed as much emphasis on resource protection as the North Pacific. (NOAA Fisheries image)

A number of regional fishing associations are joining forces to strengthen the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

The Sitka-based Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association announced last week (9-9-14) that it’s reached an agreement with the Alaska Marine Conservation Council and several east-coast industry groups to form the Fishing Community Coalition.

The new organization wants to ensure that Congress makes protecting fish stocks a priority as it prepares to reauthorize the nation’s most important law governing the harvest of seafood in federal waters.

Draft language containing proposed changes to Magnuson-Stevens has been working its way through the US House of Representatives, but the political lines became clearer when Florida’s Republican Sen. Marco Rubio introduced his version of the bill on September 16.

Read the full text of Sen. Rubio’s Florida Fisheries Improvement Act.

The top priority for Rubio is giving the regional management councils more flexibility in setting timelines for rebuilding depleted fish stocks.

This is exactly what Linda Behnken, the director of the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association, was hoping not to hear.

“There’s quite a pushback right now against the rebuilding timelines and the catch limits. You start rebuilding stocks, it means you have to catch less fish, generally, and that’s a painful process for fishermen.”

Behnken says she wasn’t expecting a Senate bill so soon, but Rubio’s paralells some language she’s seen in the House. The Fishing Community Coalition is worried about a reauthorization that merely “reaffirms the status quo” or worse “moves backward.” The Mangnuson-Stevens Act was first passed in 1976, and wasn’t considered very effective for its first two decades. But substantial amendments in 1996 and 2006 reinforced the law’s commitment to sustainability.

Behnken would like to stay the course.

“To protect the gains that we’ve made in the last two reauthorizations, for the resource. And also to look for ways to support policy that keeps a healthy resource and provides access for people who live in traditional fishing communities, to those resources.”

Behnken served three terms on the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council, one of eight regional councils established under Magnuson-Stevens. While there were always politics and tension over the allocation of fish, one thing remained unchanged.

“In this region, in the North Pacific, the council never sets any catch limits for stocks above what the scientists recommend to be optimal levels — the maximum levels that can be taken without undermining the health of the stock. That’s not the case in other parts of the country.”

“We definitely have some out here, with our Georges Bank and our Gulf of Maine cod stocks, that are a mess,” says Tom Dempsey,the Policy Director of the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance.

“And they’re collapsing right in front of us. We need improve how we manage those stocks, to give ourselves a chance at rebuilding to a point where we can have a sustainable fishery.”

Dempsey says fisheries for scallop and lobster are doing well in his region. But, groundfish, the flagship of the historic New England fisheries, are on the verge of becoming commercially-extinct. As recently as 30 years ago there were 60 boats fishing for cod throughout the summer out of Chatham, Massachusetts, where Dempsey lives. Today there are two part-time boats.

Dempsey also holds a seat on the New England Fisheries Management Council. He says there’s a tendency to distrust science in his area, and unlike Alaska, no annual stock assessment. Management decisions are sometimes being made on biological information that is several years old.

“That is a huge frustration of ours. It’s one of the central things we want to get done in this reauthorization process. And unfortunately there’s been opposition out here to the levels of catch accountability that you need to manage stocks. I say it all the time: When you’re managing fish, there are only two questions. How many fish are in the water, and how many fish are you taking out?”

Sen. Rubio’s bill includes provisions to increase funding for stock assessments and data collection, but the track record of success of Magnuson-Stevens outside of Alaska is not stellar.

Matthew Felling, spokesperson for Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski, says his boss holds some sway over her Florida colleague.

“She is someone that he relies on for guidance and for knowledge. Sen. Begich, of course, has a role because he works closely with Sen. Rubio on the Oceans Subcommittee. But as all three of them are members of the Oceans Caucus, Sen. Murkowski has been able to inform Rubio’s understanding of our waters, our fishing industry, and of our success story that we have in Alaska.”

Felling says that with the Senate likely to go into recess until mid-November, there’s no way any reauthorization will happen in this Congress. He thinks the extra time will produce a more thoughtful bill.

“Just last month at an event in the Kenai, Sen. Murkowski said that the most important priority to MSA authorization was to not just rush it and get it over with, but to do it right, dot the i’s, cross the t’s, and make sure that all possible stakeholders have their voices heard.”

Those stakeholders — according to Sen. Rubio’s office — include some of the producers, processors, and retailers trying to make the most of limited stocks. And although giving the councils “flexibility” to depart from strict conservation guidelines may become the most politically-charged idea in the reauthorization process, ALFA’s Linda Behnken says it doesn’t have to be. She says flexibility — as in the use of new data-collection tools, like cameras rather than on board observers — can actually be a good thing.

“That kind of flexibility doesn’t compromise the resource, but it’s real important to small boats and fishing communities.”

In addition to the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association and the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance, the Fishing Community Coalition includes the Alaska Marine Conservation Council, the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, and the Gulf of Mexico Reef Fish Shareholder’s Alliance.