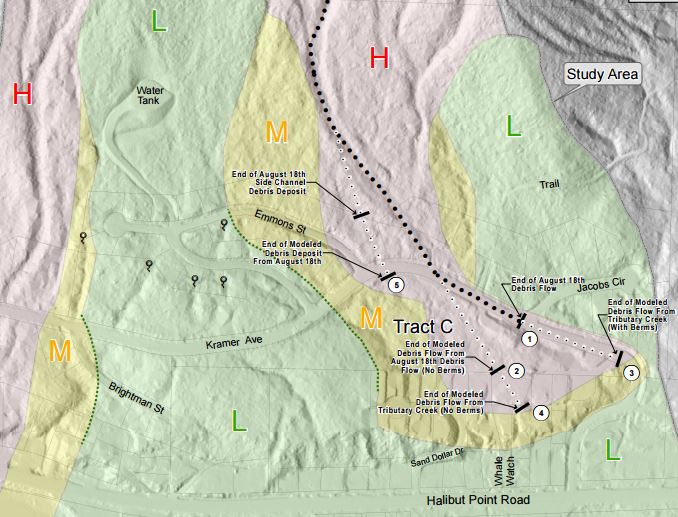

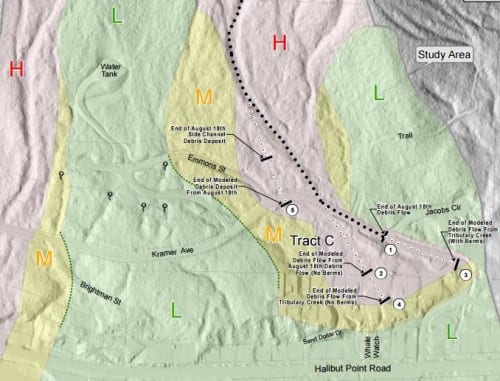

An illustration from the geotechnical study commissioned by Sitka in the aftermath of the August 18, 2015 landslides. Geologist LaPrade confirmed that there are no “no-risk” zones below Harbor Mountain.

Geotechnical consultants hired by Sitka say it’s unlikely that the city can protect residents from the type of landslides that that killed three people on Kramer Avenue last August.

An attorney on the team also argues that Sitka is not liable for damages from the slides, even though the city issued construction permits.

Attorney David Bruce was sympathetic to the tragedy that took place in Sitka last August 18. But the former assistant attorney for Seattle understood the balance that has to be struck between development and safety.

He spoke to a full house at the Sitka Chamber of Commerce last Wednesday (2-10-16).

An analysis of the landslide identified an area of weak soil and volcanic ash deposits at the top of the ridge, which failed following heavy rains that morning.

Bruce suggested that it was not going to be an isolated incident.

“This pocket of poor soil is gone. It’s at the bottom of the mountain now. It’s depleted. It’s naturally not likely that anything substantial is going to come down there anytime soon. The problem is that there are other similar formations up at the top of this ridge. So we know that there are still some up there. And I can tell you to a certainty, that some of those will give way.”

The problem is identifying where or when those failures will happen.

Bruce works for the Seattle law firm of Savitt Bruce & Willey, and specializes in municipal cases. He was joined at the chamber by Bill LaPrade, a geologist and vice-president of Shannon & Wilson, a geotechnical consulting firm.

LaPrade had prepared a detailed report of the Kramer Avenue slide area, the first geotechnical report of this scale ever done in Sitka.

As he spoke, he referred to an aerial radar image — called LIDAR — which showed the underlying terrain beneath the forest canopy.

LaPrade had some good news and some bad news.

“The lucky thing about August 18 was that there was a berm here and it deflected it. So it didn’t come straight down the hill and potentially impact these lots and these houses down here.”

LaPrade explained that a large berm of rocks being stored by contractors just below Kramer Avenue turned the slide away from home. He called it a “Rube Goldberg” device, and a happy coincidence.

And although similar structures have been built on purpose to protect slide-prone areas in other parts of the country, neither speaker recommended that Sitka rush into decisions like that.

Geologist Bill LaPrade credits a temporary berm for deflecting the slide from homes in the Sand Dollar Drive neighborhood. Building permanent mitigation measures like berms and pits has been done in some parts of the country, where tax payers agree to subsidize them.

But Attorney Bruce said it was time to start talking about risk management.

“It is my hope that this event and this information gets used to start a broader conversation in Sitka, in this room, and in other rooms like this over the coming months, about whether Sitka should undertake a more comprehensive approach to managing the set of risks that are presented in your incredibly beautiful natural setting. I mean, you sit by the sea under these gorgeous mountains — but there are some risks that are associated with this. This is not the first landslide in Sitka. The community as a whole has some sense that these hills move from time to time — that’s not news. But what happened here was that earth moved, and the mud came down, and people died.”

Bruce suggested that Sitka may want to develop a so-called “critical areas ordinance,” as Seattle has, where property owners would be allowed to develop only after obtaining their own geotechnical reports.

It would be a huge undertaking to identify risk at the level of detail that Bill LaPrade supplied for the Kramer Avenue slide, for all of Sitka. The consultants agreed that it may not be worth it.

LaPrade, the geologist, was very direct as he referred to the entire slope of Harbor Mountain, which fronts the northern end of the Sitka road system.

“There are no no-risk zones on this hillside. This whole mountainside.”

So, who is responsible when a risk becomes a reality? During questions, audience member Randy Hughey, who sits on the board of the Sitka Community Land Trust, posed this question that many area property owners in the room were thinking:

Hughey – If the city allows a property owner to build in one of the zones — or occupy a home in them — is the city assuming some sort of financial risk?

Bruce – I don’t think so, is the short answer. It’s called sovereign immunity. It’s a body of law that says when you can and can’t sue the government. In Alaska the law is pretty clear, by statute, that the city can’t be sued for either granting a permit, or not granting a permit. So if the city were to permit subdivision or construction in one of these zones that have been identified as high risk, it is my view that the city would not be liable to a claim in damages, even if the city knew it was permitting somebody to do something dangerous.

Bruce did know if that same immunity extended to developers. He said at least one lawsuit has been filed so far related to the Kramer Avenue slide.