The Sitka sac roe herring fishery operates just beyond the windows where the Board of Fish is seated. The industry wants the current management plan to stay in place, while a local cohort calling themselves the “Herring Rock Water Protectors” has aligned with Sitka Tribe of Alaska for more conservative management. (Emily Kwong/KCAW photo)

The parking lot at Harrigan Centennial Hall in Sitka is packed to the gills. That’s because the Alaska Board of Fisheries is in town reviewing over 100 finfish proposals. If passed, a proposal can changes the rules of the game for fishing and one of the major battles concerns the future of the Sitka sac roe herring fishery.

(Sound of the crowd)

Kiks.ádi clan member Louise Brady has seen the herring egg subsistence harvest diminish over her lifetime. (Emily Kwong/KCAW photo)

Sitka is the center of gravity for fish politics — at least this week. Scientists, managers, fisherman, and subsistence harvesters are sipping coffee out of plastic cups and organizing their talking points in side rooms. For lifelong Sitka fisherman Eric Jordan, who once sat on the Board, the first day is a reunion. “You visit with each other and bring up old things, old battles that you fought,” he said.

One of the biggest battles this cycle concerns waters visible outside the window: Sitka Sound, site of the Sitka sac roe herring fishery. With 48 permit holders, the Sitka herring fishery is relatively small, but controversial.

While the commercial industry harvests the eggs from inside the fish once caught, subsistence harvesters set out hemlock branches after the fleet leaves. The herring spawn and lay their eggs. But with thinning eggs on the branches, fear is escalating within Sitka Tribe of Alaska that the local stock is on the verge of collapse. The tribe began voicing concern over the spawn in 1997.

On Sunday night (01-14-17), to honor the herring, Louise Brady and other members of the Kiks.ádi clan organized a koo.éex, or potlatch. “Last year, I think, made it clear that we are close to losing our herring eggs,” Brady said.

Before the koo.éex, Brady entered the kitchen at the Alaska Native Brotherhood Hall where Nina Vizcarrando was preparing food. Opening the fridge, both were disgruntled there was only one bowl of herring eggs to go around. “This is the amount for today,” Brady said. “For 150, 200 people,” Vizcarrando added.

Meet the #AKBoF. Seven members, most based in the interior. From L to R: Fritz Johnson, Robert Ruffner (Vice Chair), Reed Morisky, Israel Payton, Al Cain, John Jensen (Chair), Orville Huntington. (Photo credit: AK Board of Fisheries)

All seven members of the Board of Fish were invited to the koo.éex and four attended: Israel Payton of Wasilla, Robert Ruffner of Soldotna, Al Cain of Anchorage, and Fritz Johnson of Dillingham. They were given gifts, like herring-shaped chocolates and traditional headbands made of yellow and red cedar.

Johnson says the board likes when different interest groups find common ground. “Come to compromise solutions where it seems there may be none readily available,” he advised. “It really enhances the process because nobody really understands local issues better than local people,” he added.

Board of Fisheries member Alan Cain speaks with Herring Rock Water Protector Peter Bradley during a koo.éex to honor herring. (Emily Kwong/KCAW photo)

Right now, compromise is days away and there’s competing herring proposals on the table. Calling for more conservative management of the fishery, Sitka Tribe of Alaska has put forward Proposal 99 (STA Proposal 99). It tells the Board to cap the harvest rate at 10%. Right now, Sitka uses a more generous formula than anywhere in Southeast, a sliding scale between 12 and 20%.

Proposal 98 (Thoms_Proposal98), sponsored by Andrew Thoms, calls for reducing the sliding scale even further (between 0 and 10%). Another option he suggests is setting aside herring for the ecosystem. “Leave a third for the birds,” he wrote in his proposal.

Sitka’s local advisory committee heard these cries for conservation. Amending proposal 99 during their November 28th meeting, they advised the Board to research what it would mean to adopt that more conservative formula used by the rest of Southeast in Sitka.

The amendment to Proposal 99 reads: The guideline harvest level for the herring sac roe fishery in Sections 13-A and 13-B shall be established by the department using a percentage that is not less than 10 percent, not more than 20 percent and within that range shall be determined by the following formula: Percentage Harvest Rate = 8 + 2 (Forecast Spawning Population Size / threshold level). The fishery will not be conducted if the spawning biomass is less than 25,000 tons.

Last week, the Sitka Assembly voted to support the conservation position of Sitka Tribe of Alaska and the local advisory committee (Res 2018-02). The math is tricky, but the important thing to know is the Southeast formula would limit fishing opportunity in Sitka.

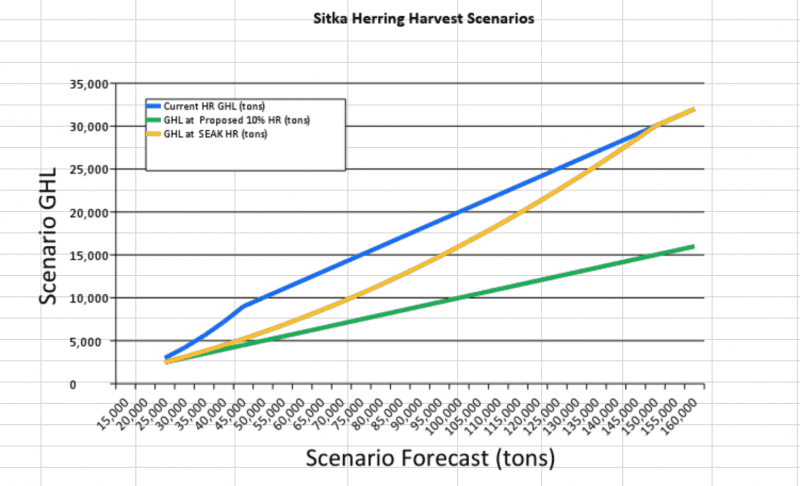

Sitka has a more aggressive harvest rate (blue line) than the rest of Southeast Alaska (orange line). The Southeast formula is more conservative, setting a lower guideline harvest level (GHL) when the biomass is low. The local advisory committee and the Sitka Assembly want the the board to consider adopting that strategy for Sitka. (Graph courtesy of ADF&G Herring Research Supervisor Kyle Hebert)

Within the 2018 forecasted mature biomass of 55,637 tons, ADF&G’s statewide fisheries scientist Sherri Dressel calculates the herring fleet’s quota would go down from 11,128 tons (20%) to 6,927 tons (12.45%). That means more herring in the ocean, but also millions of dollars in losses for the industry.

There’s no official estimate, but commercial stakeholders often say that for every ton not fished, the industry loses $1000.

Steve Reifenstuhl is the Executive Director of the Southeast Herring Conservation Alliance (SHCA), representing the fleet. He told the Sitka Assembly last week that these losses extend to the local economy. “[The means] over $100,000 in raw fish tax, bed tax, lost electrical receipts, and a huge multiplier effect to our economy,” Reifenstuhl said. “The worst thing is that this will not solve the stated issue: more herring eggs on the dock.”

He argued that the problem isn’t overfishing, but that the annual subsistence need (ANS) is too high. The ANS is currently 136,000 to 237,000 pounds.

A packed house on the first day of the Alaska Board of Fisheries in Harrigan Centennial Hall. The board will hear two days of testimony before entering the committee process and deliberations (Emily Kwong/KCAW photo)

Calling the ANS “artificially inflated,” the Southeast Herring Conservation Alliance has put forward proposal 94 (SHCA 94) to substantially lower the subsistence take. They are also recommending the board re-open the “core spawning area” closest to town to commercial fishing (SHCA 104), while Sitka Tribe wants more waters sealed off (STA Proposal 105, STA Proposal 106).

These battling proposals, with their differing opinions on health of the local herring stock, will come to a head with two days of testimony.

For those planning to take the microphone, Jordan has one piece of advice: tell the Board of Fish a story. “A compelling, credible, short story from you is what resonates,” he said. And even though it’s tempting to use all three minutes, he added, cut it down to two minutes.