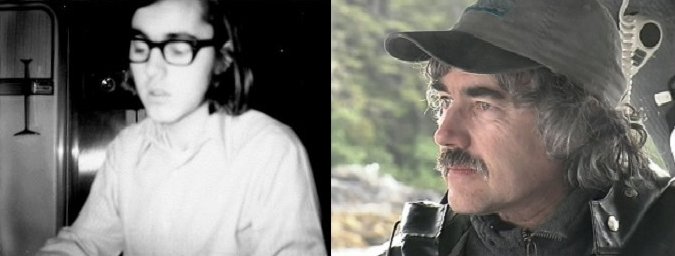

Jerry Dzugan as a 20-year old college student in 1968 (l.), and now. Asked about the fateful day in 1968 when he was caught up in Chicago rioting he says, “Well, it was more like 15 minutes!” Nevertheless, Dzugan witnessed a loss of control on both sides — protesters and police — that has shaped his views on violence ever since. (Photos provided)

2018 is the fiftieth-anniversary of one of the most turbulent years in modern American history. Some of the people who came of age then are taking time now to look back on 1968, and reflect on how the events of that year shaped them.

Sitkan Jerry Dzugan was a college student in Chicago in 1968, and witnessed firsthand the riots in the streets during the Democratic National Convention in late August. A bystander, he was nevertheless beaten and arrested during widespread efforts by Chicago police to clear the streets and restore order.

Now 70 years old, Dzugan believes it’s important to share the powerful lesson he learned that day.

So what didn’t happen in 1968? It was the year Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. The year of the Tet Offensive in Vietnam. And the year that rioters took to the streets surrounding the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. It was an unprecedented level of political violence, in an already-violent year.

Jerry Dzugan was a 20-year-old college student. A conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. He and three or four friends decided to head into Old Town, on the Northwest side of Chicago, to see what was going on.

Dzugan – I had avoided most of the protests because I wasn’t into damaging property, throwing bricks at windows, calling policemen names or anything like that. Overturning cars — that was a big one of some of my peers — but I wanted to see what was happening. It had been going on for a day or two. It was in the media. I wanted to go down one evening and see if I could find something peaceful going on.

So they drove into the city and parked. As he and his friends emerged from the car they realized that they had stopped right in front of a police line.

Dzugan – It had just formed behind us as we were parking the car, so there were police lined across the street, from bar to store. Actually I could look behind me and see them pulling people out of cars.

KCAW — These were guys with shields and billy clubs?

Dzugan — Yeah, fully-dressed Chicago police: Helmets, face guards, bullet-proof vests, mace, service revolvers, truncheons.

The rioting evolved into a street battle between antiwar protesters, police, National Guardsmen, and the US Army. Protesters feared prospective Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey would continue President Lyndon Johnson’s policies in Vietnam. (Victor Grigas/US National Archives)

Dzugan says the next 15 minutes changed his life. Rioters were starting fires in barrels, to try and block the police line. His group was trapped. Dzugan says his best option was to escape on foot.

Dzugan – It was walking out of the car into a riot, basically. And it was out of control on both sides. So I saw a side street and immediately ran down it to get out of the main street — I just wanted out of there. I remember being by myself and seeing a uniformed police officer with all the riot gear come out of an alleyway and tell me to stop. So I stopped. And he ran over to me, and what I vividly remember is the hatred in his eyes. This was a man not much older than me — maybe in his early twenties — and he was very angry about something. I don’t know what happened to him previously. But I figured that the safest thing to do was to do what he says. So I stopped and he grabbed me and started beating me with billy club. And the image I had of that was, “This is what it’s like to be in warfare, when you have the enemy in your grasp, in your eyes, and you want nothing more than to do damage.”

Dzugan says he grew up in a rough neighborhood, and this wasn’t his first fight. He managed to twist out of the officer’s grasp, and as he did so he saw an empty police paddy wagon. He dashed into it and shut the doors. It was an ironic escape, but Dzugan says “It seemed like the safest place to be at the time.”

Eventually the paddy wagon was loaded, and he and others were taken to jail overnight. A warrant for his arrest was issued after-the-fact, and when he appeared in court two months later, the judge threw out the case.

Dzugan witnessed more conflict and brutality during his night in a Chicago jail, but it didn’t turn him against police. In fact, in his current career as a marine safety trainer, he has nothing but respect for the first responders and law enforcement officers he works with.

His experience instead taught him about the futility of violence.

Dzugan – I think I was already radicalized. I think the way it radicalized me in another direction was the importance of nonviolence — stopping at the point of being physical and doing damage — which I already had a pretty good ethos about. But I saw what extreme emotions can do to people, and how they can act them out in ways that they would not normally act out. I know in their home lives they are quite different, and in their personal relationships with each other, and the need to take strong emotional feelings — which we all have — and de-escalate them. Give it time to think about it and to heal, and to find other ways to act it out.

Dzugan says one way some cultures measure time surrounding important events is by the lifespans of people left to remember them. In that respect, the Holocaust, he says, is coming to a close. In a couple of decades 1968 will reach the same threshold, and although the memories of that turbulent year will fade, he hopes the lessons do not.