Four years after a cluster of landslides — one of them deadly — struck the community, Sitka has a landslide warning system. Although it’s still a prototype, the system combines relatively simple sensor technology with the power of human social networks. Nothing quite like it has ever been done before.

August 18, 2015 was a day of reckoning in Sitka, both for the three lives lost when a slide tore through a neighborhood development, and for our loss of innocence.

Paul McArthur is the pastor of Grace Harbor Church, where rescue and recovery operations were headquartered in the aftermath of the slide.

“What was interesting for us in Sitka is that we tend to think of the mountains as our place of safety,” said McArthur. “We have a tsunami warning tower across the road from us, and we’re conscious of our vulnerability to the ocean rising. But our place of safety was the place that had now turned against us.”

Sitka’s recent landslide history

September 4, 2017 – Halibut Point Road closed by a slide near Old Sitka Rocks.

September 16, 2016 – Halibut Point Road partially closed by a slide near SeaMart.

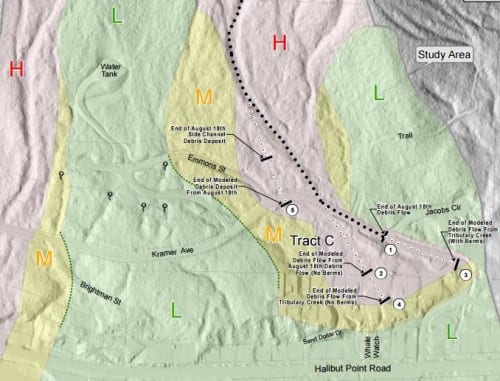

August 18, 2015 – A landslide on Kramer Avenue in Sitka leaves three dead, one home destroyed, and one heavily damaged. Another slide on Kramer Avenue does no damage. A slide on Sawmill Creek Road damages the administration building at the Gary Paxton Industrial Park.

September 18, 2014 – A 100-acre slide wipes out Forest Service restoration projects in Sitka’s Starrigavan Valley.

May 12, 2013 – A Sitka couple narrowly escapes as Redoubt Lake cabin is buried by a slide.

November 2011 – A “Mass Wasting” event destroys Beaver Lake Trail.

October 11, 2000 – A slide in the 1600 block of Halibut Point Road closes the highway and undermines a house. Also in this period, a slide above the Old City Shops property destroys a vacant former DOT Maintenance building.

August 18, 2015 was the day Sitkans realized that their picturesque city, built on shoreline between towering mountains and the Gulf of Alaska, was especially vulnerable to landslides.

What many Sitkans don’t realize was that the 2015 slides were not unique. There were three slides on the Sitka road system on August 18 — and the Forest Service estimates that there may have been around 40 more over the Sitka Ranger District, all on the same day.

Landslides are a normal, natural phenomenon in Southeast’s temperate rain forest, but Joel Curtis, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service, says the conditions that produce slides are on the rise.

“This place is famous for large amounts of rainfall,” said Curtis. “So the fact that we’re having a warmer and wetter winter, and a warmer and wetter summer, if you will — because the pattern has already started — you look at that and say ‘Gosh, there must be some correlation because it’s happening with more frequency. That also could be randomness and luck.”

On Gavan Hill, as geoscientists search for a location for the sensor.

Eli Orland (University of Oregon grad student) – I feel like I’m feeling stubborn now. (laughter, more hammering)

Up on Gavan Hill earlier in what — with a couple of striking exceptions — has been an unusually dry summer, a geoscience team is probing the soil with a piece of rebar, looking for glacial till, or bedrock — the slippery, nonporous layers underneath a debris flow — like the waterslide at nature’s frat party. With maps drawn from LIDAR data — a type of radar that uses a laser to see through trees and other forest cover to the terrain below — this team has found a site to locate one of the three landslide sensors. USGS geologist Ben Mirus confers with Annette Patton, a doctoral student at the University of Oregon.

Mirus – Because we’re only partway up the slope, these drainages are already streams or seeps, and are quite wet.

Patton – Yes.

Mirus – And as I was saying before we want someplace that’s going to be wet-and-dry, wet-and-dry, where the landslides will start. So there’s a bunch of drains that come together into this one, and then it looks like new ones starting here. So this might be a good area.

Except for the LIDAR imagery, this isn’t super high-tech stuff. In fact, it could be right out of a high school science fair. A one-meter long galvanized metal pipe with an instrument head made out of plastic sewer pipe. Simple, yet revolutionary.

KCAW – That is like Sputnik!

Corina Cerovski-Darriau (USGS geologist) – This is a tipping bucket rain gauge. This will sit on top here, the water will come through the top, and when the water fills up this bucket enough, just like a teeter-totter see-saw it will dump a set amount. So each one of these is .01 inches of rain. The sensor counts how many times it has hit either side, and we can add up how much rain there’s been.

The instrument package measures moisture levels down to a meter below the surface, air pressure, and temperature — these things have been around for years. But the wireless technology that lets them communicate is new. The scientists call it “The Internet of Things.” It might be your refrigerator, or your doorbell, talking to something with a brain, perhaps your smartphone. In Sitka, the data will be sent to devices at the Forest Service headquarters, and to the Sitka Firehall.

The brain, however, is us. The residents of Sitka.

“We’re going to build what are called decision support tools,” said Rob Lempert, a Nobel Laureate at the Rand Corporation, and an expert on community risk. “Essentially a map of the town with little slider bars that people can sit in meetings and pull and look at some of these design choices and see colors on the map, and get a sense of what’s the risk of spending the night in a shelter needlessly versus being in a situation where a landslide happens that there’s no warning.”

Lempert is one of the co-leads of this $2.1 million-dollar experiment (funded by a National Science Foundation “Smart and Connected Communities” grant). The Sitka landslide warning system is a unique marriage of meteorology, geoscience, and social science. In short, Sitkans will have a part in deciding how and when to heed a warning of a potential landslide — and use their existing social networks to spread the warning. Picture “The Sitka Bear Report” — a Facebook page with over 4,000 members noting where and when they’ve seen bears — for landslides.

“No warning system is perfect,” said Lempert. “There is a balance between failed alarms — meaning a landslide occurred you didn’t warn of — or false alarms, meaning you warn of a landslide that doesn’t happen.”

For a community that doesn’t hesitate to roll out of bed and head to high ground at the sound of a tsunami siren, building a landslide warning system that gives users a role in decision-making is novel, to say the least. But the tools and technology for this project didn’t exist even 10 years ago. And with changing weather patterns, landslides have eclipsed tsunamis as a more frequent threat in Sitka. Are we supposed to run from the hills every time it rains? This system in theory will give Sitkans — and people in any landslide-prone environment — some peace of mind.

“We wouldn’t be here if we didn’t think we were going to make a difference,” said Josh Roering, a professor at the University of Oregon, and teacher and mentor to most of the members of the geoscience team on this mountain. He doesn’t think predicting the exact timing of a landslide will ever be possible.

“But what we will be able to do is provide that real time information to people that conditions are approaching levels that might be associated with debris flow,” said Roering. “If we can provide that information to Sitkans we would be very hopeful that it can lead to the safety of the community.”

KCAW – Where are the other two sensors?

Annette Patton – There’s one on Harbor Mountain, a little bit east of the parking lot, and one on Mt. Verstovia, off of one of the switchbacks going up to the ridge…

If these three prototypes prove successful, there are plans to install more above Sitka — and to export this unique landslide warning technology to other communities. There’s no chance that it will avert disaster, but it may help avert tragedy.