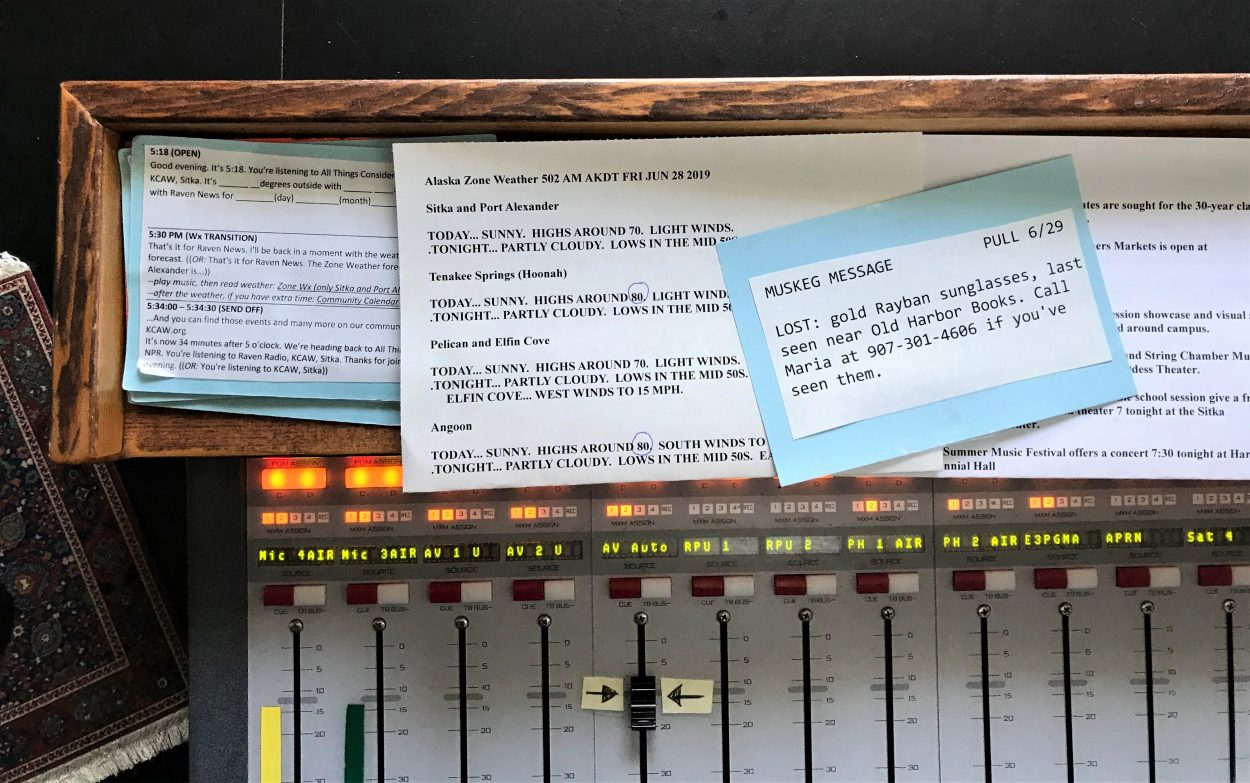

You hear them on the radio all over Alaska. Around Sitka, they’re called “Muskeg Messages”; elsewhere, they’re “Bushlines,” or “Caribou Clatter.”

The over-the-air messages Alaskans send on their public airwaves have been in existence as long as the stations themselves — but (and this may come as no surprise), they are illegal.

Instead, as former KCAW summer news intern Nina Sparling reports, a handshake agreement between a powerful US senator and the chairman of the FCC opened up a brand-new form of communication in some of the remotest places in the country.

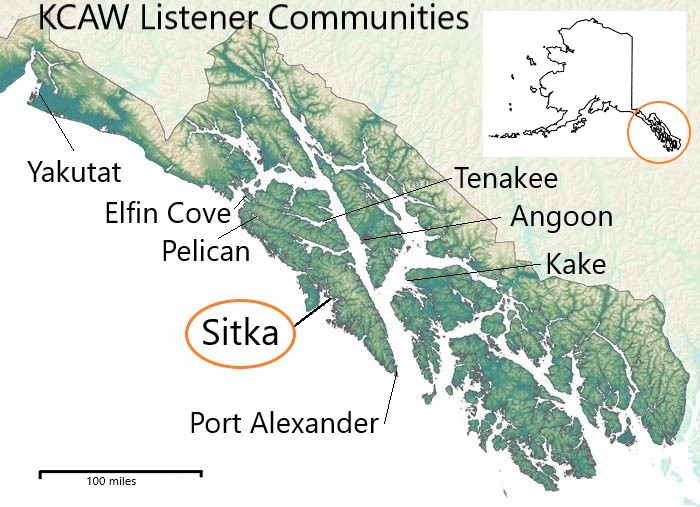

Rain Van Den Berg left Juneau for a cabin outside Tenakee Springs, Alaska in 1994. She was in the bush, beyond the reach of modern services like telephone lines, roads, and Main Street. There was one payphone four miles up the coast in town and no service in the cabin. Every ten days or so she would kayak to Tenakee for supplies, a bath in the local hot springs, and to use the one payphone in town to talk to anyone she could get a hold of. Between phone calls, Rain religiously tuned into KCAW, the public radio station in Sitka.

“What I didn’t realize was how much I would crave the sound of human voices,” she said. “The radio provided a bridge to people.” She appreciated the news and music, but she listened for something else: muskeg messages.

I met her on a flight from Seattle to Sitka. I had two backpacks, a bike helmet, and wide eyes. Rain wore her long hair straight down her back, brushing the waist of a knee-length floral skirt. We had seats next to one another and even though the plane was half empty we both stayed put. Her partner Allison Hill sat next to her.

I told them I was moving to town to work at the local radio station for the summer. “Oh, we love KCAW,” they said, one after another.

Then, Rain asked me if I knew what muskeg messages were. That was the first time I had heard the word muskeg. She described how newscasters and DJs would read these messages over the air intended for particular people, or for a community of listeners. Anna Mekkie in Port Alexander “found a baby river otter and needs advice on how to care for it.” Holly tells her mom, Judy Thorssin, “that Palmer, Alaska misses her.” Rain wasn’t sure if the station still sent them.

I had never heard a radio station do this before: collect messages from its community and broadcast them. I knew radio as a way to hear what happens beyond my immediate circle, not as an integral part of it.

I made a mental note as the plane began its initial descent to the tarmac. I took grainy pictures of the water from my iPhone. It looked like the mountains in the North Cascades where my grandparents lived and died, but with just the peaks poking out, the valleys filled with saltwater and salmon.

Sometime after I started blinking less at the crystalline water and learned the names of the city assembly members, I asked my new coworkers about muskeg messages. Rob Woolsey turned around on his wooden stool. He confirmed that the station still did them. Katherine Rose warned that they weren’t that common. She estimated fifteen or twenty muskeg messages total in the three years since she first came to Sitka for the same summer internship.

She mentioned a rumor about someone using muskeg messages to traffic drugs or people sometime in the 1990s. I envisioned breaking some big story about how criminals took advantage of a small-town radio tradition to do business.

There are a lot of these kinds of stories about muskeg messages: snippets of something someone remembers hearing on air, a vague memory of local goings-on. They circulate in the community and shift in retelling. No archive of the messages exists.

I abandoned hope of uncovering some untold story of trafficking conducted over the airwaves. I learned that muskeg messages belong to a whole family of message services that radio stations across Alaska provide to their listeners. Each has a name for the messages it takes and shares: KTNA’s Denali Echoes, KBBI’s Bushlines, KFAR’s Tundra Topics, KCAW’s Muskeg Messages, and so on.

Then, I found something that surprised everyone at the station: every time a station sends a muskeg message, or Bushline, or Denali Echo, it breaks the law.

“First of all, I have to tell you that it’s illegal,” Rich McClear tells me. He wears thick plastic-framed glasses and has a voice that’s equal parts resonance and rasp. McClear founded KCAW in the early 1980s.

Broadcast services cannot be used to relay personal messages, McClear explained to me. The Federal Communication Commission draws a distinction between broadcasters, like radio and television stations, and common carriers, like telephone lines. Broadcasting is a one-to-many, not a one-to-one service, so broadcasters are technically not supposed to carry messages intended for an audience of one.

“Now, since broadcasting started in Alaska, Alaskans have ignored this rule,” McClear said.

Most people agree that commercial broadcast in Alaska started with Augie Hiebert founded KFAR in Fairbanks in 1939. The communications infrastructure that existed was tied to the military. Roads, telephone cables, and electricity connected military outfits in places like Anchorage and Fairbanks. The stations that popped up in cities had high-powered AM signals that could reach hundreds of miles into the bush. Alongside news and music, KFAR ran a program called Tundra Topics.

“It unified the interior,” Augie’s daughter Cathy said. “People traveling by dogsled, by snow machine, they have a radio, and they’re going between point A and point B and there is nothing else around.”

Writer John McPhee was one of those people between point A and point B with nothing else around. He tuned in to Tundra Topics while working on his 1976 book Coming into the Country.

“As a public service in the absence of telephones, Alaskan radio stations spray messages around the bush,” McPhee writes. Radio was the only way to get word to people living in cabins and dry towns in the furthest reaches of the state. And people used the service. McPhee noted examples:

To Brenda Carter. I’ll be in late tomorrow night. I love you, John.

To Mr. O at Eagle from J.R. at Fairbanks. Please clean the snow off my roof.

Passed police exam. Love, Jim.

Planning to have the baby born at Lynette’s cabin. Ellen and Jim Frazier. Eagle.

To Jan and Seymour on the Yukon from Mom in Anchorage. Are you there?

Please, Isaac, don’t drink. We’ll be getting married next week.

High-powered AM signals like KFAR’s traveled hundreds of miles –– but entire swaths of the last frontier survived without broadcast service whatsoever well into the 1970s. The first radio stations were commercial: they needed big listening communities to stay afloat. And telephone service improved and the business consolidated many commercial stations phased out their personal message programs

About the time that McPhee traveled the Bush in eastern Alaska a different kind of radio started to spread across the state: public radio. The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 opened the airwaves to state and federal funding nationwide. In the decades that followed, community stations started up across rural parts of Alaska and they brought the messages with them.

Public radio went where commercial stations wouldn’t: to rural towns and villages without access to other kinds of communication infrastructure. Public broadcasting became a way for stations to grow where the bottom line was hard to maintain: the corners of Alaska without deep pockets, where modern services were slow to arrive.

“I’m not sure that some of the more urban people really have a real good understanding of how important it can be for people,” said Steve Heimel. He has been in public broadcasting in Alaska just about as long as there have been public broadcasters.

“If you are really living in an isolated place and this radio is your connection to the world, that’s really worth quite a lot,” Heimel said. The legality of the messages mattered little to station managers: their rural listeners needed them.

Once, the FCC wised up to Alaska’s public radio messages. Rich McClear remembers when the chairman of the FCC came to Alaska to meet with broadcasters and then-Senator Ted Stevens. At a speech before the Alaska Public Radio Network and the Alaska Broadcasters Association, the Commissioner told the audience that he knew had been listening to the radio in Alaska and heard the messages. He realized they were illegal but recognized the public service they provided. The Commissioner then pledged to make them legal.

McClear and Senator Stevens cornered the chairman after his speech and asked him to leave the messages alone. They didn’t want to have to go through the legal proceedings, which could take years. The chairman saw his point. He shook hands with Senator Stevens and McClear and continued his visit.

“It’s jokingly been called the Stevens exemption since then,” McClear said. Other station managers reported a vague recollection of Senator Stevens winning protections for the radio messages. But no one remembered that meeting of the Alaska Public Radio Network and Alaska Broadcasters Association; McClear can’t recall which FCC chairman it was. Phone calls and emails to the Commission itself yielded little clarity, but the legal issue hasn’t come up again for broadcasters in Alaska. The story passes from station to station, unconfirmed and quiet.

When McClear moved to Alaska decades, Port Alexander, a community of just under a hundred people on the southern tip of Baranof Island, had a single telephone. “If it would ring, no one would answer,” he said. “It was in the store or the post office or something. And so how do you reach people?”

Often, by radio.

I knew there would be bears and salmon in Sitka otherwise arrived unprepared. I figured people lived up here to escape convenience and efficiency. I didn’t understand what that meant when Rain told me about muskeg messages on my flight. Most of Baranof Island still lacks cell service. So radio stations –– despite easier and more reliable alternatives –– still alert an entire community of personal, often inconsequential, business.

Rain listened for these messages every day when she lived in the cabin outside Tenakee Springs. She used the radio to keep track of time and to hear human voices. Muskeg messages –– it didn’t matter that the people receiving them were strangers — provided that.

“Just hearing what was happening in other people’s lives, it meant a lot to me at that time,” she said.

I had told the whole radio station I was working on this story. Muskeg messages were part of their routine — an inconsequential piece of working in community radio in Alaska.

The calls came infrequently. Sitkans rely on a Facebook group called Sitka Chatters to canvas or bicker with the community. But every once in a while, the calls come in. One morning in the first week of July, I arrive to Max eager to tell me something. He was the program director at the station for two years.

“Nina!” he says.

“Max!” I said, hanging up my coat to avoid the paper shredder. “Hi, Katherine,” I added over my shoulder

“I have a muskeg message for you!” he said. He hands me a blue 3×5 index card and Katherine looks up from her desk.

“Caring for a baby river otter! Looking for advice or assistance, or possible placement with a new caretaker. Please Call Anna Mekki in Port Alexander,” I read aloud. I paused.

“What’s a river otter?” I asked. Max burst out laughing, and Katherine pulled up an image on her computer. They look more like weasels or beavers than sea otters. I propped the notecard with the message on it up against my computer and flipped through the police blotter.

That evening, I tucked the muskeg message behind the pages of local news. I read it over the air and pictured Anna Mekkie at home with a river otter wrapped in an old bath towel, lapping water out of a bowl, recovering. I have never been to Port Alexander but imagined the single payphone that Rich McClear used in the 1980s, in a rusted box on the outside of the one bar in town, and Anna in a house, waiting for the phone to ring.

Later in the summer, three people called to leave messages for Judy Thorssin in two days. I got snippets of her story: they were calling from Palmer. She was moving or emptying a storage chamber.

“From: Sofia and Lylah Bahri. To: Judy Thorssin, AKA Nana. We love you and we send you lots of kisses. We want you to come back soon!”

I read the message over the air and hoped there was a portable radio in the storage unit or that Judy happened to be driving right at the end of the evening newscast.