Alaska has no shortage of marine predators – from orcas, to Steller sea lions, to salmon sharks. Over the past few years, researchers have identified a new, lesser-known predator that may play a key role in keeping Alaska’s kelp forests healthy.

Third-year graduate student Nikita Sridhar reaches deep into a tank in the basement lab of the Sitka Sound Science Center looking for what she calls an “underappreciated predator.” These creatures are such effective hunters that when they enter an area, it’s like you can hear the screams underwater,” Sridhar says. “Everyone’s just trying to flee the scene.”

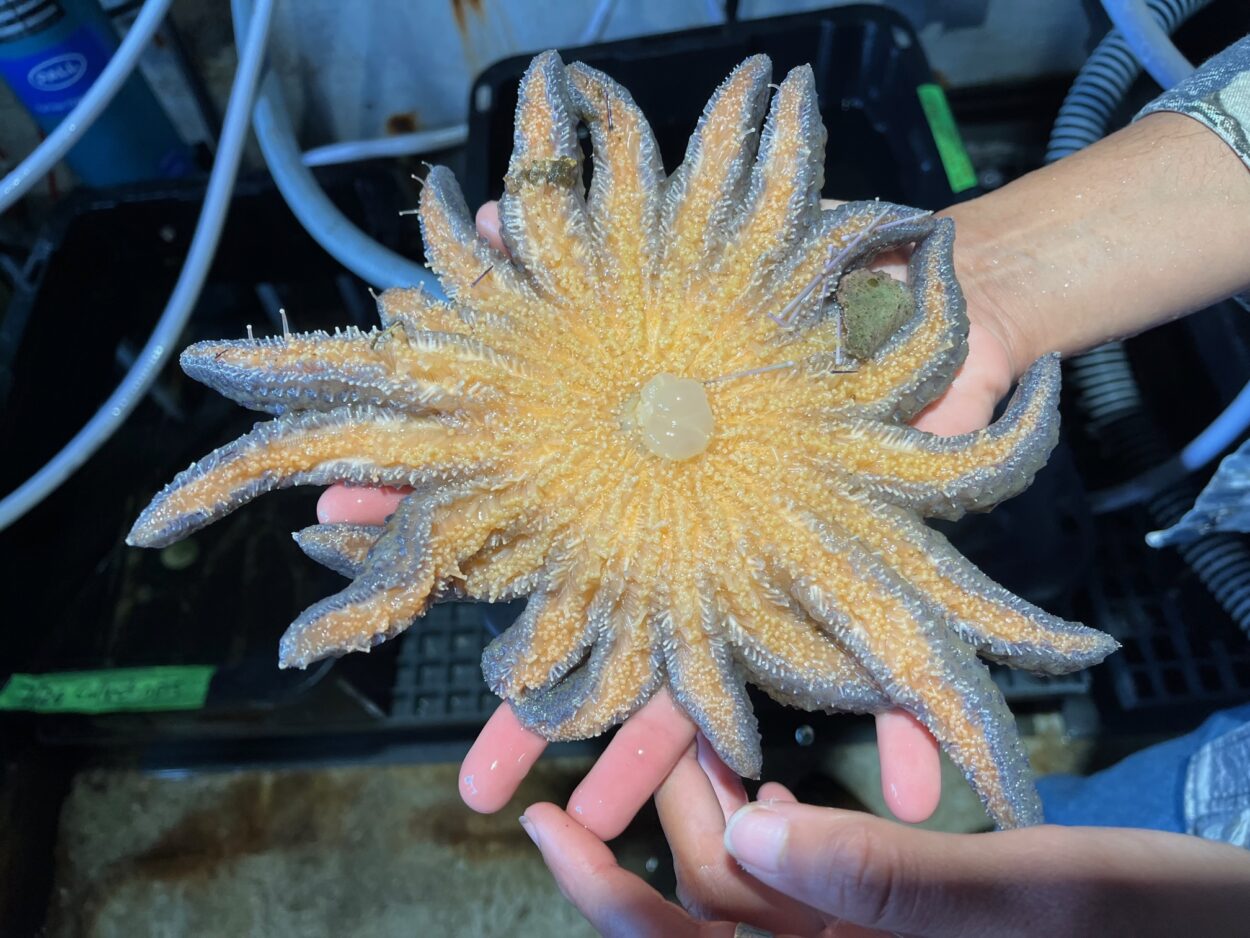

Sridhar wrestles the creature out of the tank and holds it up to the light – a dinner-plate-sized purple sea star.

Sunflower stars, or Pycnopodia species, are the focus of Sridhar’s research this summer through her work with Professor Kristy Kroeker at University of California, Santa Cruz. Sridhar hopes to build on previous research to learn more about how sunflower stars could help protect coastal kelp forests.

Sea stars may not intimidate us humans, but to a population of sea urchins, they’re a formidable predator.

“They basically throw their stomachs out, they lift up their arms, and then part of their stomach from the underside is thrown out,” Sridhar said. “And then they engulf the urchin.”

The sea star in her hands shows recent evidence of such grisly events — its stomach protrudes out of its body, and crushed urchin spines dot its many arms.

While unfortunate for the urchin, this kind of predation is good for the ecosystem. Urchins eat kelp, and too many urchins can decimate kelp forests that sequester carbon, which mitigates the effects of climate change, and provide homes to many critters.

“They’re like skyscrapers that create homes for all these different animals,” Sridhar said.

Keeping kelp forests healthy requires a balance of kelp-eating ‘grazers’, like urchins and abalone, and predators – like sea stars – who eat the grazers.

“If you lose one part of this puzzle – for example, you lose an important predator – then you might have too many grazers,” Sridhar said.

That’s happened before – a decline in the population of sea otters, a well-known predator of urchins and other kelp-eating critters, led to the spread of “urchin barrens” along the Pacific coast, where urchins have mowed down entire kelp forests.

Now, researchers are trying to figure out if, and how, other predators such as sunflower stars could play a complementary role in protecting the kelp forests.

Sunflower stars eat urchins, but Sridhar suspects that they may also affect urchin behavior in other ways. In her work this summer, she is trying to figure out if the mere presence of a sea star can cause urchins to eat less kelp.

“Just sensing this predator might lead to the urchins being scared into eating less kelp,” Sridhar said. “They might be investing their energy into running away from the predator or hiding in little crevices rather than just roaming on the seafloor, eating kelp as they please.”

In one experiment, Sridhar situates a caged sunflower star in the center of a tank full of urchins. She wants to see if the urchins move away from the cage, or eat less kelp, when they sense that a sea star is nearby. Out in Sitka Sound, her team is running similar experiments, tracking the path of a sunflower star and seeing how long it takes for urchins and abalone to return to those spots, or “whether that slime trail of a sea star is so strong that they’re too scared to come back, basically.”

If sunflower stars serve as vigilante kelp guardians, that’s exciting news for the kelp forests, especially if the sea star population rebounds. Sea star wasting disease has plagued the West Coast over the past decade, dissolving huge swathes of sea stars. Sunflower stars were hit especially hard by the epidemic.

Sridhar said they’ve seen more mature sunflower stars around Sitka Sound this summer than expected. That is, at least tentatively, cause for celebration.

“It’s exciting that we are seeing them this summer, and hopefully these populations persist through time,” Sridhar said. “We’ll see.”

Sridhar doesn’t have results back yet, but she’s excited to see how these sunflower stars might help protect kelp forests by creating what she cheerfully calls a “landscape of fear” for urchin populations.